Is this a world of chaos? Is life simply extended hospice care?

Discovering the Origins of Joy by Reading Genesis

The Western story, which we inhabit in every classroom, cubicle, zoom call, and supermarket—the story we through podcasts and social posts—begins with this foundational assumption: the world starts with chaos. Your life. Your world. Your story—all of our stories—begins and ends with turbulent pain. Our job is to survive it as comfortably as possible. Human life is hospice care.

Nietzsche said there’s nothing: this is all there is and it’s horrifying. Do your best to survive it.1

Freud added: The aim of all life is death—we have an innate drive toward destruction.2

Darwin proposed: The existence of all living things is bound by survival of the fittest and most adaptable.”So, adapt to an environment that wants to crush you. To exist is to survive and pass your genes on the next.

Hemingway said, “Life breaks everyone—the brave and the good and the cowardly and weak.” He championed a stoic view of existence: life is meaningless until an individual attaches meaning to his life with his own efforts. It’s up to us to make life meaningful.

Descartes philosophized that we have to survive existence by having the right perspective. Tupac said it more clearly: “Keep your head up, things are gonna get better.”3

Survive. Manufacture meaning. Keep your head up. Bravely embrace the nothingness. This is the story we inhabit. It’s the story we live. It’s the trajectory of human existence we assume. Get through it and make the best you can out of it however you wish.

But what if that’s not quite right?

There are so many moments when the story of chaos feels like fantasy not reality. When you’re playing with your kids in the back yard on a warm summer evening as the sun sets and the noise of family-wide laughter joins the chorus of birds chirping you feel at home in the world. There’s a sense that this is life and the chaos and death of the world is the aberration. Or, when a child is diagnosed with cancer, we don’t shrug and say: “that’s life. I guess they were a weak one.” No, we fight for their life and desperately seek a renewal of every cell in their being so they might live. When you stand at a gravesite a haunting intuition overtakes you: “this isn’t right.” Our senses tell us the tomb is foreign to our purpose.

What if the world isn’t supposed to be spiraling towards death? What if all living things aren’t bound by survival of the fittest but the thriving of all creatures big and small? What if, instead of hospice care, life is intended for joy?

Ancient Contrast

Standing in contrast to our modern story is the text of the Bible which says and has said since the ancient days of a freed slave people in the desert: The world was formed with intention and it was good. The origin story of the cosmos is filled with joy.4

Before there was pain, death, and destruction, there was life. There was joy in work, love in relationships, communion with creator, and restful delight. Your story, my story, the story of humanity doesn’t begin with pain. The first cause isn’t chaos. The initiation of the universe was creative contentment.

The Bible claims humanity is formed. Made. Fashioned. God created humanity—not for sorrow—but for life.

The prophet Isaiah describe the intention this way: “The people, whom I formed for myself, so that they might declare my praise.”5 St. Paul in his first century letter to Ephesus wrote “We are God’s handiwork, created in Christ Jesus”.6

Rereading Genesis

The clearest evidence of a world created for delight instead of death is found in the poetry and narratives of the first chapters of Genesis. They take readers into the formation of a world for worship, humanity for praise, and the origins of both the destruction of peace and the promise of God to restore all things—even joy and satisfaction. This story makes the most sense of our desperate longing for goodness and our angst in chaos. You can disagree with it, but you’ll need to find some story that makes sense of your desires for goodness.

To understand this claim you must reread the origin story in the world found in the Hebrew Scriptures. The gap we have with lasting joy in our humanity is filled with our ignorance of and isolation from this ancient holy text. Our lives have great access to chaos and crises. The image of a joyful world formed for beauty and goodness feels as foreign as life on Jupiter.

I want to try to bridge that gap for you by bringing you into contact with the beginning, the language God uses to describe it, and the context in which he speaks it. Over the next several weeks, I’ll dive deep into the first eleven chapters of Genesis to draw us into the claim that humanity exists because of intentional goodness and for the sake of joy. We’ll also see the origin of sorrow as it explains the pain, agony, and chaos of every human relationship and the world itself.

But first, a few caveats for my friends who struggle with the first pages of the Bible because of the historic debates on scientific accuracy or simply a difficulty in reading such an old and foreign style piece of writing. Of course, if you feel completely settled, you can skip all of this and move on to the next article when it comes out next week.

Caveat #1: This Isn’t the Text You Think It Is

Anytime you read Genesis in our modern world, there is some level of detachment. The pile of dustups between Darwin and denominations towers over our reading of Genesis. There’s the ringing in our ears of college professors: “you can believe in science or you can believe in the myth of religion.” Or maybe you’re reminded of cute children’s Bibles with brilliant colors and surely you can’t find the meaning of life here! More to the point, our expectations of Genesis is an argument for how old the earth is and how fast it was made.7

The first readers of Genesis weren’t concerned with the age of the soil and dirt beneath their feet. Their concern was not a play-by-play vision of the mechanics of the universe. Instead, they were grappling with the divine purpose of their existence and whether it was simply to live, serve, and die or if somehow their life had greater meaning. Or, if Yahweh, was a different type of god that formed the world for something great—not to fill it with slaves, but to fill it with humans that shared in god’s dignity and creative power.

This is what’s lost when we try to cram 21st century scientific theory and European enlightenment into inspired words to expose us not to the mechanics of the formation of the world, but to expose us to God.

One of the great false critiques advanced in the western world is that the Bible is a very bad science text. The Bible is not a scientific text at all other than it speaks to and inhabits the world that we also inhabit.

In fact, the Bible is a very fine piece of advance literature revealing the nature and purposes, character, and voice of God. That’s what it’s about and that’s what it is. It would be like saying Victor Hugo’s Les Miserable is a very bad French History text, or Star Trek is a bad spaceship manual. There are elements of French History you can glean from Hugo and there are plenty of space travel ideas taken from the Enterprise; however, they weren’t intended for those purposes. It isn’t even close their main objective. In the same way some people have taken the scientific revolution to dissect the Bible and demonstrate it can’t reveal truth on grounds it wasn’t intended to.

It is okay for people who don’t believe the Bible to come to it with cynicism and critique from their own cultural moment and heritage.8 This has always been the case. But if you really want to know what it’s getting at, you have to come to it on the terms it sets. You can watch a movie like Iron Man and spend the entire time critique the likelihood of a billionaire creating a new mechanical heart in the desert; but it’s better to watch it as a story that takes place in the comic world of Marvel. When you do that, you might recognize, the story isn’t proposing new medical technology, but about what happens when someone’s weakness, their heart, is made new and becomes their strength.

Genesis is better than Marvel and its claims concern the longings of the human heart. The first chapters in Genesis offer emphatic, humbling, and loving truths that draw you under the authority of God—an authority springing from an encounter with reality.

What the Bible does ask of us, physicist, musician, doctor, lawyer, barista, and computer programer, is to come—not to examine it—but to have it examine us. To come expecting truth that informs how we process our world. To come expecting a confrontation with who we are and how we live. It demands an approach that, at some level, is looking for the substance of life and willing to submit life to the God of the Bible.

What’s at stake when we read the first pages of Genesis is not the timeline of our world but the nature of the God making this world and then subsequently the world’s purpose and our purpose in it. It is better to read asking: were we made for anything, what is this world about, and what happened to make it such a mess? It’s best to come asking: who is this God and what is he like?

Caveat 2: Inhabit the Ancient World

So, don’t check your brain at the door. Don’t choose between God and science. Don’t neglect your intuition to read and understand what you’re reading the way you try to read and understand anything you read. Read this as masterpiece literature that has the capacity to bring you into contact with the world as it real is and the relational being who initiated it and sustains it.9

You have to know where the author is coming from, who they were writing to, what their situation was, what their history was, and the context of their moment. It’s also helpful to think about their culture and the cultures around them. Lastly, it’s important to know how they use language, grammar, style, and genre.

The Context of Genesis and the History of the Moment

The first five books of the Bible do not arrive—both tradition and logic speak to this—as a scroll descending from the sky. Genesis is earthy, coming up from the context of a people in a desert in a moment. The challenge of reading and understanding these ancient texts is the interdisciplinary nature of it. It’s literature in history, of history, and shaped by history.

The first five books of the Bible are Moses’ books written during the wanderings of a recently liberated slave nation who spent five-hundred years in complete captivity to the super power of that age.

They experienced a level of generational trauma we have few reference points in our modern world. Their world was a world of torture. The pharaohs operated as gods who commanded their movements, their life trajectories, and even their family growth. Their existence was for Pharaoh as he built places of worship for himself. Nothing was done and nothing could be done to help. There was no one looking out for them. There was no intentional concern extended to them—only the brute force that demanded a submission and resignation to a life of labor.

The myths and gods of Egypt ruled all of life. They were in charge of the sun, the crops, the rain, and fertility. Humanity existed to perform for these gods. The gods of Egypt were angry, unsatisfied, and restless. Pharaoh was their incarnation.

When this slave people were freed it was exciting. God took on all the gods of Egypt and walked them through water. Yahweh vanquished Pharaoh. The people of Israel sang songs to God and danced. Life was so good. Their future seemed good.

Until it wasn’t and they realized they were in the wilderness. They left the tyranny of forced labor, infanticide, and neglect for a prolonged subsistence nomadic life in the desert.

The liberated slaves received food from heaven, water from rocks, and the doldrums of daily wandering. A pillar of smoke and column of fire led the way. Extreme highs and lows. This is the human context and environment in which the first words of the Bible were uttered and heard. It’s during the decades in the wilderness that Moses spends time praying, communing with God, and writing by the work of God, the words we have before us.

The Language of Genesis

We cheaply use language.10 Our words are valued in fractions of pennies. It costs nothing to produce words of nonsense. The digital age is the age of endless content of discounted vocabulary. In the ancient world, every word and phrase came with rich meaning and intentional use. The building of narrative and poetry was greeted with the same level of excellence as latte art and curated home decor. This means it doesn’t come to us like a tweet, an email, or chatGPT. Genesis comes to us as an expansive narrative. When every syllable, sound, and stroke of the pen reshapes our imaginations to see the world as it ought to be.

Read and wonder

Listen to the words of Genesis and allow your imagination to drift away from the origins of matter and consider the original intention of matter and man. Is this story compelling? What if this description of God forming the world for endless goodness, flourishing, and praise, is not only a nice thought but the true ontological purpose of all things—including you.

Citations and Further Reading

See his essays: On the Genealogy of Morality and Beyond Good and Evil

Freud, Sigmund. Beyond the Pleasure Principle. International psycho-analytical Press, 1922.

Topac’s song: “Keep Ya Head Up”

This claim is not only in contrast to our worldview, but the ancient world in which it was written.

Isaiah 43:21

Ephesians 2:10

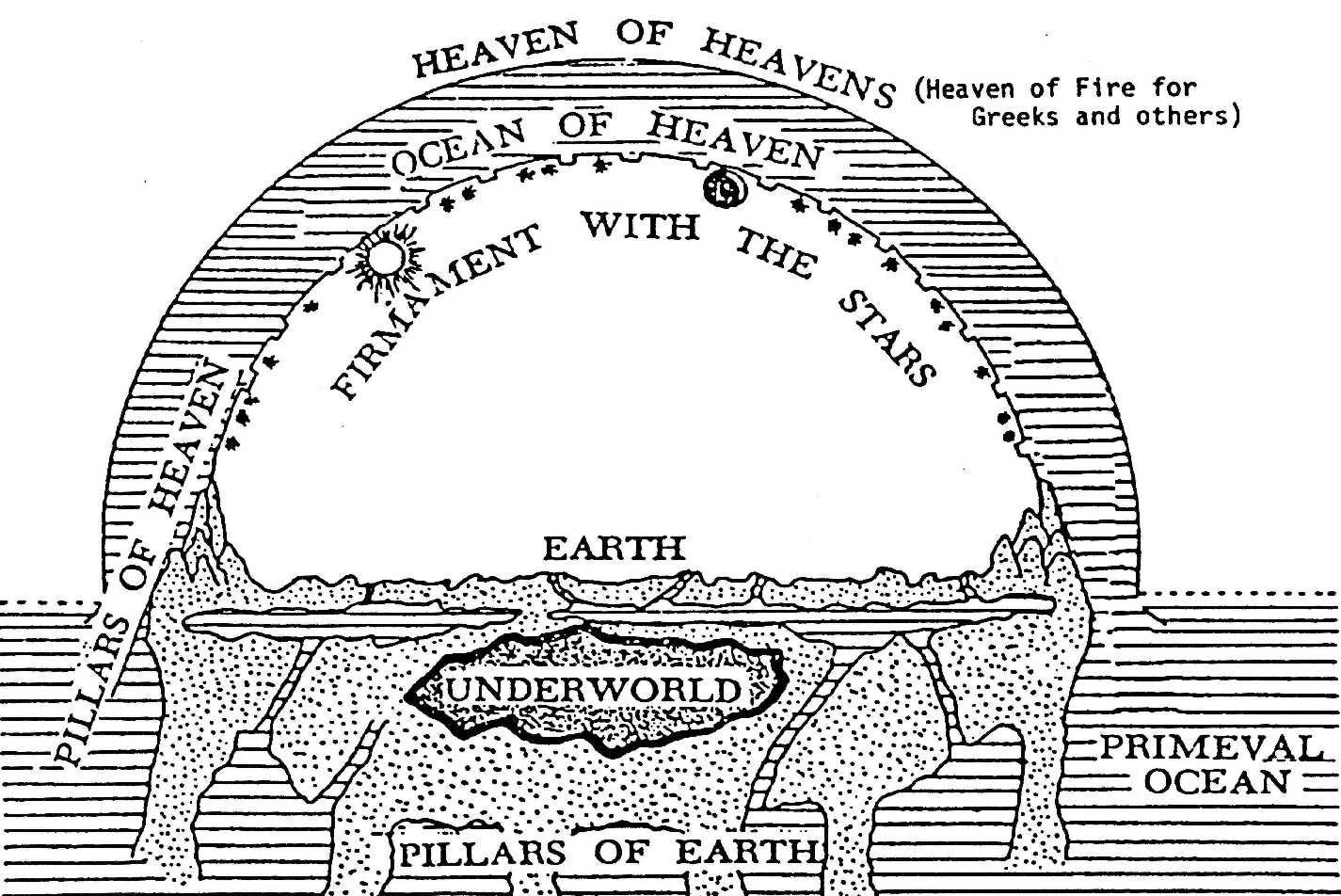

Many scholars have drawn out diagrams of the cosmology described in the Bible. It’s quite comedic knowing what we know today of what our planet truly looks like. Here is one such drawing. Again, you have to ask, were they trying to draw the universe in the same Stephen Hawkins or Albert Einstein were? Was it for the same purpose as Galileo?

The cosmology described by Moses in the Pentateuch and referenced by David in the Psalms is the cosmology of the day and surrounding cultures. God doesn’t challenge that, not because God doesn’t care, but because that’s not his purpose in these words. God uses words and a framework they would have understood to tell them something powerful about who he is that transcends chronologies, timelines, and scientific theory. For more, see The Lost World of Genesis by John Walton.

There is an issue with Christians who respond to the Scientific Revolution with a submission to it by addressing the Bible is a science textbook. They attempt to cram the words of Genesis 1 through a Western 21st century biochemistry grading matrix. What happens is the interpretive principles we follow in all other passages are jettisoned. We don’t ask about author, intent, context, original audience, and most importantly, genre. Instead we ask, how can we prove the Bible is an accurate scientific text. When this happens Christians begin taking stands and twisting the text beyond its intention. When we do that we miss the Bible itself and we’re doing more mutilation of the biblical texts than the scientist who blows them off. It’s like taking someone’s poetry , handing it to a physicist and asking them to grade it, not as poetry that reveals the author and truths of the world, but grading it as a physics term paper on gravity and then saying the poem proves gravity exists. For more, see John Lenox’s book, Cosmic Chemistry or Where the Conflict Really Lies by Alvin Pantinga.

When I say, “read as literature” I truly mean to read as we would any text to understand its meaning. The same skills of reading Anna Karenina ought to be used to understand theme, plot, and discover meaning when we read the skillful narrative of the Old Testament.

See Robert Alter’s writing in both The Art of Biblical Poetry and The Art of Biblical Narrative.